Beth Shean

Beth Shean

From the Fountain of Harod to Beisan, the modern representative of Beth-shan, is a pleasant ride of about nine miles. The road leads down the valley of Jezreel, through fields and meadows of extraordinary fertility. The soil is rich and water abundant; the people, too, who now possess it seem to be industrious. . . . There are several large fountains in the valley which send copious streams to the Jordan. Owing to the abundant waters and the damming up of some of the streams, a large section of the valley round Beth-shan is a morass. The whole valley is among the most productive in Galilee. But it has some serious drawbacks. The heat is oppressive in summer, owing to the fact that it lies considerably below the level of the sea and is shut in between the ridges of Moreh and Gilboa. Malarious fever is prevalent, and the resident natives seem feeble and sickly. The plain is also to some extent exposed to the raids of the Arabs from the east of the Jordan, though of late, owing to increased vigour and watchfulness on the part of the Turkish Government, they are kept in check, and cultivation is progressing. (Source: Galilee and the Jordan, p. 193, emphasis ours.)

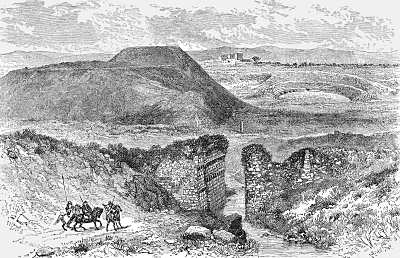

Beth Shean from South, Site of Recent Excavations

The ruins of Beth-shan are very extensive, covering an irregular area nearly three miles in circuit. They are intersected by deep ravines, through which perennial streams flow. When rain falls heavily the streams become foaming torrents. The site of the old city is singular. It is a natural terrace at the eastern end of the valley, where it drops down abruptly three hundred feet or more into the great valley of the Jordan. On the north, spurs of the range of Moreh stretch out to the ruins; on the south, but at the distance of a mile or more, rises the steeper and higher ridge of Gilboa. The stream from the Fountain of Harod flows through the ruins in a very deep ravine, and it is joined by another smaller stream and ravine from the south. Between the two, at the point of junction, is the most striking natural feature of Beth-shan—a conical hill two hundred feet high, with steep and, in places, precipitous sides. This was the ancient acropolis, and a position of great natural strength. It was defended by walls and towers, portions of which still remain. (Source: Galilee and the Jordan, pp. 194-95.)

Source: Galilee and the Jordan, p. 194.

Beisan (Beth-Shan)—East Bridge, Citadel, and Theatre

. . . a street or road lined with colonnades led round the base of the hill and over the southern ravine to a theatre some distance up the bank. Many of the columns and portions of the entablature lie on the ground amid heaps of rubbish and jungles of thorns, thistles, and rank grass. This seems to have been the Via Recta of the Roman city, like those of Palmyra, Gerasa, and Damascus. Every important Roman city in the country appears to have had such a street. The principal part of the ancient city lay to the south of the citadel-hill, in the valleys, and on the table-land beyond. The Theatre is one of the most perfect, and at the same time one of the very finest, specimens of pure Roman architecture in Western Palestine. On the bank above it is a large Hippodrome, and around it are the remains of several temples and other public buildings; but all so completely ruined and so overgrown with thorns and rank vegetation that it would be impossible without much labour and excavation to ascertain their original design. (Source: Galilee and the Jordan, p. 195.)

Beth Shean Excavations, Remains of Byzantine Portal

The Philistines occupied the city at an early period, and it long continued to be their principal fortress in the north of Palestine. Standing on the top of the citadel, and closely examining the topography of the extensive panorama around me, I was able more fully to understand how the “valiant men of Jabesh” accomplished their daring feat of taking down the bodies of Saul and his sons from the wall. They were doubtless fastened to the most conspicuous part of the wall, probably near or over the principal gate. From the base of the citadel a deep ravine runs down to the Jordan valley. Up this it was comparatively easy for a little band of active mountaineers to ascend in the night, to scale the wall, to remove the bodies, and to carry them away beyond the Jordan, most probably without being seen. (Source: Galilee and the Jordan, p. 196.)

Beth Shean, Village

The modern village of Beisan is poor and very dirty. The houses are mostly of mud, and the general aspect is that of a village on the banks of the Nile. There is one large and rather imposing stone house, occupied by the Turkish governor, and probably built for him. It is distinguished by the high-sounding name Serai, “palace.” On the occasion of my last visit to Beisan I was invited to remain in it during my short stay. So much was I impressed by the name “palace,” and by an invitation from “the governor,” that I entered and sat down on the floor; for there was neither chair nor carpet, nor mat, nor furniture of any description. Of course, after a very formal salute to “His Excellency,” who squatted in a corner, and who very kindly ordered a sumptuous repast to be served up, I withdrew to my tent, though the thermometer stood at about 98° Fahr. The heat was more tolerable than the fleas and other creatures with which the palace swarmed. Not far from the Serai is a ruined mosque, apparently once a church. (Source: Galilee and the Jordan, p. 196.)

See Caesarea, Beth Shean, Nazareth, Huleh Valley, or Sea of Galilee

At BiblePlaces, see Beth Shean