Holy Fire Ceremony

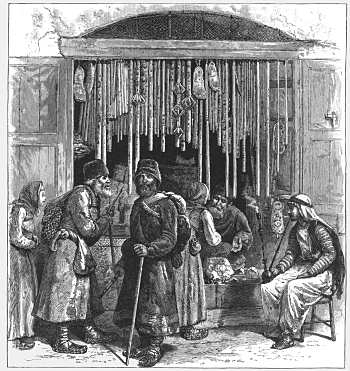

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, p. 22.

Pilgrims of the Greek Church Buying Candles

No description of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre would be complete without some notice of the ceremony of the “Holy Fire,” which, to the disgrace of Eastern Christianity, is enacted at the present day . . . . The Chapel of the Sepulchre rises from a dense mass of pilgrims, who sit or stand wedged round it; whilst round them, and between another equally dense mass, which goes round the walls of the church itself, a lane is formed by two lines, or rather two circles, of Turkish soldiers stationed to keep order. For the spectacle which is about to take place, nothing can be better suited than the form of the Rotunda, giving galleries above for the spectators and an open space below for the pilgrims and their festival. For the next two hours everything is tranquil. Nothing indicates what is coming, except that two or three pilgrims who have got close to the aperture keep their hands fixed in it with a clench never relaxed. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, p. 23.)

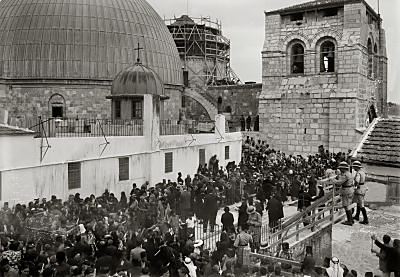

Ceremony of Holy Fire on Roof of Greek Convent

Source: American Colony: Jerusalem

It is about noon that this circular lane is suddenly broken through by a tangled group rushing violently round till they are caught by one of the Turkish soldiers. It seems to be the belief of the Arab Greeks that unless they run round the Sepulchre a certain number of times the fire will not come. . . . First [one] sees these tangled masses of twenty, thirty, fifty men, starting in a run, catching hold of each other, lifting one of themselves on their shoulders, sometimes on their heads, and rushing on with him till he leaps off, and some one else succeeds; some of them dressed in sheep-skins, some almost naked, one usually preceding the rest as a fugleman, clapping his hands, to which they respond in like manner, adding also wild howls, of which the chief burden is ‘This is the tomb of Jesus Christ! God save the Sultan!—Jesus Christ has redeemed us!’ What begins in the lesser groups soon grows in magnitude and extent, till at last the whole of the circle between the troops is continually occupied by race, a whirl, a torrent of these wild figures, like the witches’ Sabbath in ‘Faust,’ wheeling round the Sepulchre. Gradually the frenzy subsides or is checked, the course is cleared . . . (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, pp. 23-25.)

Source: American Colony: Jerusalem

Holy Sepulcher, Orthodox Holy Fire

. . . and out of the Greek Church on the east of the Rotunda a long procession with embroidered banners, supplying in their ritual the want of images, begins to defile round the Sepulchre. . . . In one small but compact band the Bishop of Petra (who is on this occasion the Bishop of ‘the Fire,’ the representative of the patriarch) is hurried to the Chapel of the Sepulchre, and the door is closed behind him. The whole church is now one heaving sea of heads. . . . By the aperture itself stands a priest to catch the fire; on each side of the lane hundreds of bare arms are stretched out like the branches of a leafless forest—like the branches of a forest quivering in some violent tempest . . . . At last the moment comes. A bright flame as of burning wood appears inside the hole—the light, as every educated Greek knows and acknowledges, kindled by the bishop within—the light, as every pilgrim believes, of the descent of God himself upon the Holy Tomb. Any distinct feature or incident is lost in the universal whirl of excitement which envelops the church as slowly, gradually, the fire spreads from hand to hand, from taper to taper, through that vast multitude, till at last the whole edifice, from gallery to gallery and through the area below, is one wide blaze of thousands of burning candles. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, pp. 25, 27-28.)

Church of Holy Sepulcher, pilgrims with Holy Fire

Source: American Colony: Jerusalem

It is now that, according to some accounts, the bishop or patriarch is carried out of the chapel in triumph, on the shoulders of the people, in a fainting state, ‘to give the impression that he is overcome by the glory of the Almighty, from whose immediate presence he is supposed to come.’ It is now that the great rush to escape from the rolling smoke and suffocating heat, and to carry the lighted tapers into the streets and houses of Jerusalem, through the one entrance to the church, leads at times to the violent pressure which in 1834 cost the lives of hundreds. For a short time the pilgrims run to and fro, rubbing the fire against their faces and breasts to attest its supposed harmlessness. But the wild enthusiasm terminates from the moment that the fire is communicated; and perhaps not the least extraordinary part of the spectacle is the rapid and total subsidence of a frenzy so intense . . . . Such is the Greek Easter—the greatest moral argument against the identity of the spot which it professes to honour—stripped, indeed, of some of its most revolting features, yet still, considering the place, the time, and the intention of the professed miracle, probably the most offensive imposture to be found in the world. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, p. 28.)

See also Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Authenticity of the Holy Sepulcher, History of the Holy Sepulcher, or Via Dolorosa.

At BiblePlaces, see Church of the Holy Sepulcher