Muslim Customs

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 172

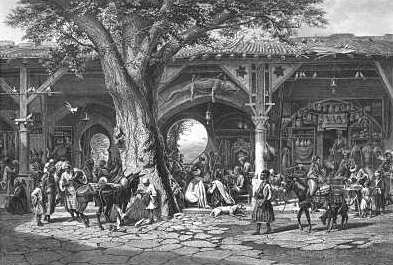

A Street in Damascus

The main streets are densely crowded with passengers in all sorts of costume and colour . . . men and beasts jostling against each other in endless confusion. This motley street life is at once amusing and bewildering, a moving panorama, a perpetual carnival. It is the very opposite of the sight on the Paris Boulevards, London Bridge, or New York Broadway. For the Orientals, judged by Western notions, do everything the wrong way: they sit cross-legged on the floor or on the earth, they eat with the fingers, they keep their women veiled and out of public sight, they take off their shoes in the mosque and keep on their fez or turban; they are dressed in flowing robes, and for the poorer classes any scrap of cotton or linen, or silk or blanket, or shawl or sash, serves for a covering; but they have a native air of dignity and courtesy, and always look picturesque. There are no ruling fashions which obliterate distinctions, as they do in the West; everybody follows his own taste or whim, and maintains his individuality. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, pp. 172-74.)

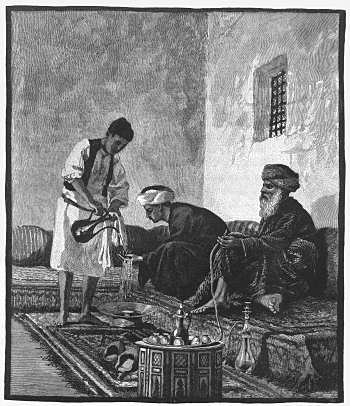

Ablutions After a Mid-Day Meal

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 3, p. 77

Of all people of the East it may be said, "except they wash their hands diligently, eat not" (Mark vii. 3). And this is particularly necessary where knives and forks are not used, and each one "dips his hand into the dish" with his neighbour. When the dinner or supper is ready a servant brings in a large metal basin (tisht), with a perforated cover and a raised perforated receptacle for soap in the middle, and places it before the chief or most aged person present, who takes the soap and rubs his hands, while a stream of water is poured gently over them from a long-spouted ewer (ibrîk); the water disappears through the pierced cover, so that when the basin is carried to a second person no soiled water is visible. The same process is repeated after a meal. It is an after-dinner washing of hands that is shown in the illustration . . . . The elder man, who is blind, has already performed the ablution, and is waiting for his nargîleh to be lighted, after which coffee will be served. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 3, p. 86.)

Beersheba Feast

Immediately afterwards supper was served. A wooden bowl, rather shallow, but about a yard in diameter, filled with steaming rice boiled in butter, was placed on the ground at a little distance from us. Metal dishes containing meat, eggs, vegetables, and cream were added to the feast, round which the sheikh, the priest, and the elders of the village assembled. They ate quickly and silently, dipping pieces of their thin leathery loaves into the dishes of fried eggs and cream, tearing the tender morsels of meat to pieces with their fingers, dipping their hands together into the mound of rice, and skilfully and neatly taking it up in pellets. When they were satisfied, they retired one after the other to wash their hands and to light their pipes. Their places were quickly taken by the younger men and boys in turn, and when they had all finished the servants gathered round, eating from the same dishes . . . . The fragments that remained after the feast were not carried away until all the men and boys of the village had eaten there, but the women and children ate elsewhere and in private. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 3, pp. 115-16.)

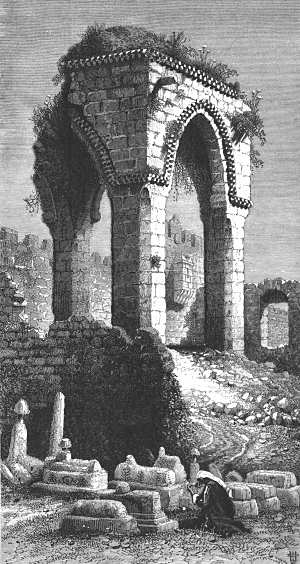

In the Mohammedan Cemetery, Jerusalem

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, p. 69

As I passed across the great court [of the hospice], on my way out, I heard a terrible sound of lamentation. The little fever-stricken boy had just then died. A group of women stood in the doorway, and others quickly gathered round them from the neighbouring rooms. Then they together suddenly uttered the death-cry, called wilwâl, a peculiarly mournful cadence, with shrieks and pauses at regular intervals. This cry has been transmitted from one generation of mourners to another, and is probably exceedingly ancient; it may even be the echo of the great cry which was heard throughout all the land of Egypt when all the first-born were smitten (Exod. xii. 30). Throughout the East, the instant after a death has taken place the women present proclaim it by loud lamentations; all the women who hear it flock to the house of mourning and join in the "death cry," which cannot possibly be mistaken for any other sound. Professional mourners, who are "skilful in lamentation," are employed by wealthy people to assist the volunteers (see Amos v. 16). (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 2, p. 164.)

See Arabs, Bedouin, Muslim Religious Practices, Mosques, Jews, Samaritans

At BiblePlaces, see Dome of the Rock