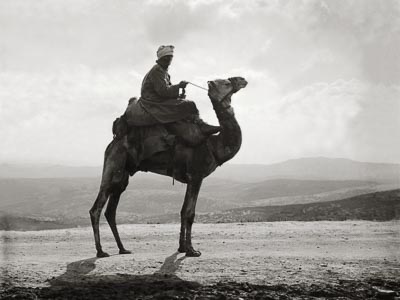

Travel in the Desert

Camel, Ship of the Desert

Day after day found us urging our camels to their utmost pace for fifteen or sixteen hours together out of the twenty-four, under a well-nigh vertical sun, which the Ethiopians of Herodotus might reasonably be excused for cursing, with nothing either in the landscape around or in the companions of our way to relieve for a moment the eye or the mind. Then an insufficient halt for rest or sleep, at most of two or three hours, soon interrupted by the oft-repeated admonition, 'If we linger here we all die of thirst,' sounding in our ears; and then to remount our jaded beasts, and push them on through the dark night, amid the constant probability of attack and plunder from roving marauders . . . . The days wore by like a delirious dream, till we were often unconscious of the ground we travelled over and of the journey on which we were engaged. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 4, pp. 93-95.)

Sandstorm in the Desert

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 4, p. 15

The day after leaving 'Ayún Músa was at first within sight of the blue channel of the Red Sea. But soon Red Sea and all were lost in a sand-storm, which lasted the whole day. Imagine all distant objects entirely lost to view;-the sheets of sand fleeting along the surface of the Desert like streams of water; the whole air filled, though invisibly, with a tempest of sand, driving in your face like sleet. Imagine the caravan toiling against this, the Bedawín each with his shawl thrown completely over his head, half of the riders sitting backwards, the camels meantime thus virtually left without guidance, though from time to time throwing their long necks sideways to avoid the blast, yet moving straight onwards with a painful sense of duty truly edifying to behold . . . . Through the tempest, this roaring and driving tempest, which sometimes made me think that this must be the real meaning of a howling wilderness (Deut. xxxii. 10) we rode on the whole day. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 4, p. 12.)

Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 1, p. 216

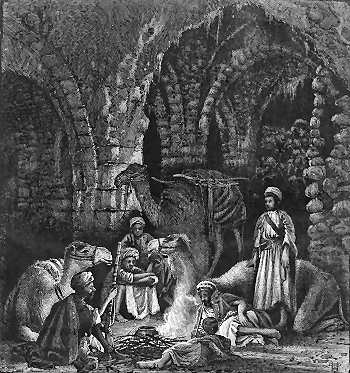

Halt for the Night, Khan of El Bireh, Ancient Beeroth

The loneliness is very intense. Yet there is an intermittent murmur of laughter and merriment from the group of Arabs round the encampment fire, which begins to shoot forth a cheerful light on the white canvas of our two small English tents. And who are these Arabs? and why should one be obliged to have their company, or at any rate the company of any except those to whom the camels belong and who act as camel-men? The track is not hard to find, and the watering places are well known. These Arabs are the ghufará, or protectors, without whose escort the traveller would not be safe in the Peninsula or in the Desert. They belong to the tribes which have the legitimate right to give protection to the Convent and to travellers. The country under their protection is accurately defined and recognised by other Bedawín; and while under their care and within the limits of their protectorate one is safe. (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 4, p. 5.)

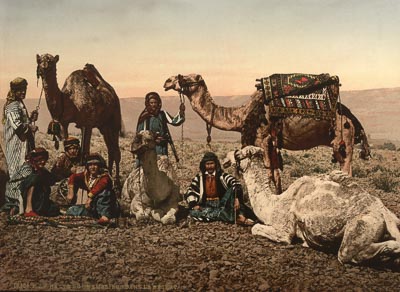

Halt in the Desert

Source: The Holy Land in Photochrom

Mr. Palgrave . . . warns one not to accept without much allowance the favourable pictures which travellers draw sometimes of the good faith and the hospitality of the Bedawín. Of the first he writes-"Deeds of the most cold-blooded perfidy are by no means uncommon among these nomades, and strangers under their guidance and protection, nay, even their own kindred and brethren of the desert, are but too often the victims of such conduct. To lead travellers astray in the wilderness till they fall exhausted by thirst and weariness, and then to plunder and leave them to die, is no unfrequent Bedawín procedure. . . . . Thus, for example, a numerous caravan, composed principally of wealthy Jews on their way across the desert from Damascus to Bagdad, was, not many years since, betrayed by its Bedawín guides. The travellers perished to a man, while their faithless conductors, after keeping aloof till they were sure that thirst and the burning sun had done their work, returned to the scene of death, and constituted themselves the sole and universal legatees of the moveable goods, gear, and wealth of their too-confiding companions." (Source: Picturesque Palestine, vol. 4, p. 42.)

See Camels, Travel by Sea, or Bedouin

At BiblePlaces, see Animals of the Bible or Southern Wildlife